Easter Is Not Named After Ishtar, And Other Truths I Have To Tell You.

Easter Is Not Named After Ishtar, And Other Truths I Have To Tell You

The Eightfold Path and the Educator

The Eightfold Path and the Educator.

The above link is a wonderfully insightful post from a fellow teacher.

The Buddha’s Words on Kindness (Part 3)

Within my last post I wrote about ‘The Four Noble Truths’ and ‘Ethics in Buddhism’ which, along with Wisdom and Meditation, make up the Threefold Path. Today I wanted to finish my notes on my time at the Buddhist Centre by looking at the third fold – Wisdom.

Wisdom

Buddhists believe that everything / all phenomena (dharma) bear the following three ‘marks’ (Pali: tilakkhaṇa; Sanskrit: trilakṣaṇa) of existence:

- Impermanence (anicca)

- Unsatisfactoriness (dukkha)

- Non-Self (anattā)

Impermanence (anicca) in Buddhism means that everything is ‘signless’ and changing. We should be aware that each breath is unique during meditation, formed from different molecules and shared with others. We should reflect that we are made from elements that are constantly exchanging with the universe, and we are part of the flow. The Buddha said “we are made of rice and bread”. Life is change.

Kūkai or Kōbō Daishi 空海・弘法大師 (774–835) was one of Japan’s most famous intellectual figures. He founded the Shingon school of Buddhism (真言宗), and was also a prolific writer and artist. The following poem from Kūkai illustrates the idea of impermanence:

昔日剃頭今長髪

出家二種心惟重

紅花緑 實一株物

君見春秋顔色同世理无 常人如此

心縁不動大道通

長江萬里以相答

雖爾處身如虚空Long ago you received the tonsure; now your hair is long.

Of these two forms of renunciation heart is important.

Red flowers and green fruits are of the same trunk.

You see that in spring and autumn their colours are the same.The principle of the world is impermanence; people are like this.

If mental cognition stops moving the Great Way is ascertained.

A long river may extend ten thousand miles, but the waters all pass together.

Although this may be so, where the body abides is like empty space.

For more information about Kūkai and his work see here.

Unsatisfactoriness (dukkha)

As mentioned in my last post, the first noble truth is the truth of dukkha. The Pali term dukkha (Sanskrit: duhkha) is typically translated as “suffering”, but the term dukkha has a much broader meaning than the typical use of the word “suffering”. Dukkha suggests a basic dissatisfaction pervading all forms of life, due to the fact that all forms of life are impermanent and constantly changing. Dukkha indicates a lack of satisfaction, a sense that things never measure up to our expectations or standards.

The emphasis on dukkha is not intended to be pessimistic, but rather to identify the nature of dukkha, in order that dukkha things may be overcome. The Buddha acknowledged that there is both happiness and sorrow in the world, but he taught that even when we have some kind of happiness, it is not permanent; it is subject to change. And due to this unstable, impermanent nature of all things, everything we experience is said to have the quality of dukkha or dissatisfaction. Therefore unless we can gain insight into that truth, and understand what is really able to give us happiness, and what is unable to provide happiness, the experience of dissatisfaction will persist

Non-Self (anattā)

In Buddhism, the term anattā (Pāli) or anātman (Sanskrit: अनात्मन्) refers to the notion of “not-self” or the “illusion of self”. In the early texts, the Buddha commonly uses the word in the context of teaching that all things perceived by the senses (including the mental sense) are not really “I” or “mine”, and for this reason one should not cling to them. In Buddhism there are five functions or aspects that constitute the human being (the five “khandhas“) and the Buddha repeatedly emphasizes not only that the five khandhas of living beings are “not-self”, i.e. not “I” or “mine”, but also that clinging to them as if they were “I” or “mine” gives rise to unhappiness.

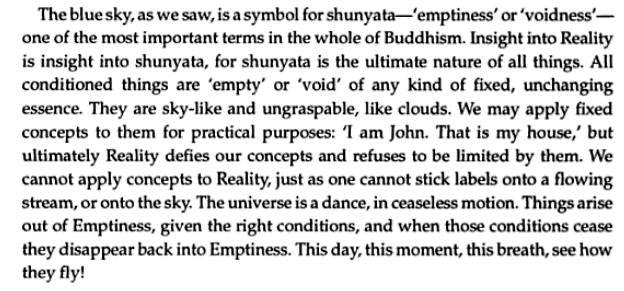

These concepts are explained in the following paragraph from “Meeting the Buddhas: A Guide to Buddhas, Bodhisattvas and Tantric Deities” by Vessantara. The paragraph mentions Śūnyatā, (Sanskrit, also shunyata; Pali: suññatā) which, translates loosely into English as emptiness /openness /thusness and refers to the absence of inherent existence in all phenomena. This is complementary to the Buddhist concepts of not-self.

I really like the above paragraph as it truly demonstrates that a label on a person artificially fixes them but they will always be more than your interpretation. It reminds me of the following quote:

I have never experienced another human being. I have experienced my impressions of them. – Robert Anton Wilson

There will be more from RAW in future posts I’m sure! I thought this would be my last post from my time at the Buddhist Centre, but I still have a few notes which haven’t quite fitted in anywhere and may also be included in the future. The more I read about Buddhism the more appealing and fascinating it seems – I have a lot more reading to do!

Related articles

- The Buddha’s Words on Kindness (Part 2) (inf0junkie.wordpress.com)

- The Karaṇīyamettā Sutta: The Buddha’s Words on Kindness (Part One) (inf0junkie.wordpress.com)

The Buddha’s Words on Kindness (Part 2)

What do you think this means?

All will be revealed below…..

Buddha’s Lists (and why he needed a blog like this one)

There are a great many lists in Buddhism, and the following paragraph explains why:

The Buddhist scriptures of the Pali Canon consist of three sections or baskets; the Suttas, which are the Discourses; the Vinaya, which is the rules of the monks and nuns; and the Abhidhamma, the higher doctrine of the philosophy and psychology of the teachings written only in ―Ultimate Truth‖ language of analysis. The complete Pali Canon is roughly about 20,000 pages long. Setting aside the stories and the biographical / historical information in the scriptures and you are virtually left with only a whole pile of lists from the Buddha and long explanations about the lists. The Buddha was like a scientist observing reality and Ultimate Truth from the deepest levels of Insight and enlightenment of this mind-body. The lists are the break-down of the doctrines, concepts, reality, and the mind-body.

Thus, we find all of the Buddha‘s teachings and a summary of the 20,000 pages of scriptures in the lists…. The Buddha literally had hundreds of lists.

The Complete Book of Buddha’s Lists – Explained (page 22)

The above book was a lucky find when I was ‘Googling’ some of the notes I had taken at the Buddhist Centre for further information. It is a free download as the book had been prepared and printed for no profit. This is because the teachings from the Buddha are seen to be so valuable that no price could ever be attached to it. (In the vipassana tradition teachings are offered free of charge, but voluntary donations called dana are accepted.) I am yet to read the complete text but have dipped in and out and have used the book quite a bit when researching the information contained in this blog. I would definitely recommend it.

During my time at the Buddhist Centre we looked at Buddhism as a Three Fold Path as follows:

- Ethics (Morality)

- Meditation (Concentration)

- Wisdom

I was interested to learn about the first fold – ‘Ethics in Buddhism’ – as it is the foundation of the other two folds. I have since read that the Threefold Path is actually a simplified version of the ‘Eightfold Middle Path’ and can be expanded as follows:

- Right Understanding (Wisdom)

- Right Thought (Wisdom)

- Right Speech (Ethics / Morality)

- Right Action (Ethics / Morality)

- Right Livelihood (Ethics / Morality)

- Right Effort (Meditation / Concentration)

- Right Mindfulness (Meditation / Concentration)

- Right Concentration (Meditation / Concentration)

The Five Precepts

Ethics in Buddhism (the moral issues 3 to 5 of the eightfold middle path above) are also found in what Buddhists call the “Five Precepts”.

Buddhists voluntarily take and recite these, and believe will lead naturally to happiness. These not commandments, but a voluntary guide to summarize the moral part of the Eightfold Middle Path:

1. Abstention from killing or causing to kill.

2. Abstention from stealing.

3. Abstention from sexual misconduct.

4. Abstention from telling lies.

5. Abstention from alcoholic drinks, drugs, or intoxicants that cloud the mind.

Since the five precepts and the Eightfold Middle Path are voluntary, violators are not considered “sinners” or evil in any way. Some Buddhists are not vegetarian, do drink alcohol, take drugs, or have multiple sex partners. This does not make them “bad” people as is sometimes the label in other belief systems.

Buddhists believe that gradually through learning, knowledge, and meditation practice, the practitioner finds the value and happiness of voluntarily accepting the precepts and the Middle Path. To avoid attachment to things, such as ideologies, letting go is a virtue, so that one does not judge others who still may not be fully following the precepts.

Arthabandhu described these precepts to us in detail, and how they can relate to modern life. He also discussed the ‘positive/negative’ alternative version as follows:

- Nourish deeds of loving kindness (+ve) / Abstain from violence (-ve)

- Nourish open handed generosity (+ve) / Abstain from taking the not giving (-ve)

- Nourish stillness, simplicity and contentment (+ve) / Abstain from sexual misconduct (-ve)

- Nourish truthful communication (+ve) /Abstain from false speech (-ve)

- Nourish mindfulness; clear and radiant (+ve) /Abstain from intoxicants (-ve)

The Four Noble Truths

The Buddha taught that life is Dukkha (“suffering“). However, we create this suffering from our own mind, body, actions, feelings, perceptions, and thoughts. We tend to cling and have too much attachment to things that are full of suffering and impermanence. Thus, we find no lasting happiness. This concept is detailed in the Four Noble Truths:

1. Life is suffering

2. Suffering is caused by unreasonable expectations

3. Suffering ceases with the ceasing of unreasonable expectations

4. The way to reasonable expectations is the Eightfold Middle Path

(The Pali term dukkha is typically translated into English as “suffering”, but the term dukkha has a much broader meaning with no direct translation. Dukkha indicates a lack of satisfaction, a sense that things never measure up to our expectations or standards. I have used the term “suffering” here to aid the understanding of the equation that follows, as that is the term used in the original article, but the more I read about dukkha, the more I prefer the term ‘dissatisfaction’ as its closest literal translation.)

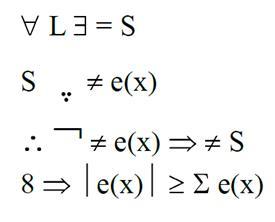

As a maths graduate I couldn’t resist including the equation which opens this blog. I came across it in The Complete Book of Buddha’s Lists (page 33). Shown below is the Four Noble Truths written as a mathematical expression.

Variables:

L = “un-enlightened” life

S = suffering

8 = eightfold middle path

All of the other symbols are mathematical symbols. The translation of the above mathematical expression with the definition of the mathematical symbols in italics:

1. For all life, that there exists, there is suffering.

2. Suffering exists because of unfulfilled expectations.

3. Therefore, it follows that, the logical negation of false expectations leads to no suffering.

4. By following the eightfold middle path, you have the absolute value of fulfilled expectations which are greater than or equal to the sum total of all expectations.

I must admit, I haven’t checked the Maths but on first glance I trust it to be true. In Buddhism, The Four Noble Truths are an understanding of the origin and cessation of anguish. This term “anguish” being utilised here as it describes the feeling when our expectations are not met. When we have unrealized expectations we have anguish, stress, frustration, and suffering. Buddhists see a way out of anguish and suffering and this is in the fourth Noble Truth, which is the Path.

By not placing such unreasonable expectations on others we avoid suffering.

By not placing unreasonable expectations on ourselves we avoid suffering.

For example, although not a Buddhist, Bill Gates followed a formula similar to the one shown here. He is supposedly quoted in interviews saying that he and his company “under-promise and over-deliver.” This is another way of saying keep the expectations low and then exceed them.

There is a statistical formula used in the social sciences to test research findings and statistical significance. This statistic is called chi square and if the value is high enough there is said to be a statistical significance. Statistical significance means that it is unlikely the research results were the result of sampling error or unlikely to be from chance. This chi square test deals with comparing actual, observed results with what was “expected” and is applied to the Four Noble Truths here (page 35).

Next time: The Third and Final Fold – Wisdom

Related articles

- The Karaṇīyamettā Sutta: The Buddha’s Words on Kindness (Part One) (inf0junkie.wordpress.com)

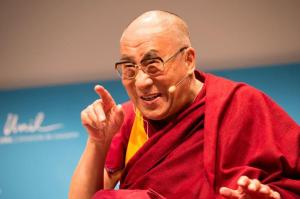

“My religion is kindness…”

His Holiness the Dalai Lama is a man of peace. In 1989 he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for his non-violent struggle for the liberation of Tibet. He has consistently advocated policies of non-violence, even in the face of extreme aggression. He also became the first Nobel Laureate to be recognized for his concern for global environmental problems.

His Holiness the Dalai Lama is a man of peace. In 1989 he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for his non-violent struggle for the liberation of Tibet. He has consistently advocated policies of non-violence, even in the face of extreme aggression. He also became the first Nobel Laureate to be recognized for his concern for global environmental problems.

His official website is well worth a look, but allow plenty of time as it is filled with messages, teachings, interviews, photographs and videos that will inspire and encourage. For shorter snippets of inspiration try his facebook page.

“I believe that the purpose of life is to be happy. From the moment of birth, every human being wants happiness and does not want suffering. Neither social conditioning nor education nor ideology affect this. From the very core of our being, we simply desire contentment. I don’t know whether the universe, with its countless galaxies, stars and planets, has a deeper meaning or not, but at the very least, it is clear that we humans who live on this earth face the task of making a happy life for ourselves. Therefore, it is important to discover what will bring about the greatest degree of happiness…..From my own limited experience I have found that the greatest degree of inner tranquility comes from the development of love and compassion.” – His Holiness the Dalai Lama

His Holiness has three main commitments in life:

- On the level of a human being, His Holiness’ first commitment is the promotion of human values such as compassion, forgiveness, tolerance, contentment and self-discipline. All human beings are the same. We all want happiness and do not want suffering. Even people who do not believe in religion recognize the importance of these human values in making their life happier. His Holiness refers to these human values as secular ethics. He remains committed to talk about the importance of these human values and share them with everyone he meets.

- On the level of a religious practitioner, His Holiness’ second commitment is the promotion of religious harmony and understanding among the world’s major religious traditions. Despite philosophical differences, all major world religions have the same potential to create good human beings. It is therefore important for all religious traditions to respect one another and recognize the value of each other’s respective traditions. As far as one truth, one religion is concerned, this is relevant on an individual level. However, for the community at large, several truths, several religions are necessary.

- His Holiness is a Tibetan and carries the name of the ‘Dalai Lama’. Tibetans place their trust in him. Therefore, his third commitment is to the Tibetan issue. His Holiness’ has a responsibility to act as the free spokesperson of the Tibetans in their struggle for justice. As far as this third commitment is concerned, it will cease to exist once a mutually beneficial solution is reached between the Tibetans and Chinese. However, His Holiness will carry on with the first two commitments till his last breath.

The Karaṇīyamettā Sutta: The Buddha’s Words on Kindness (Part One)

I have an interest in all faiths and beliefs of others and I am always open to learn about them. I am fortunate that my partner shares my interest and we have recently attended some introductory workshops at the Nottingham Buddhist Centre together. Even though I class myself as being agnostic, the concept of Buddhism appeals to me as Buddha was not a god or a prophet; he was a human being like all of us. He didn’t preach and dictate; he taught love, generosity and kindness through practical experiences and through his own efforts he gained Enlightenment:

“Do not believe in something because it is reported. Do not believe in something because it has been practiced by generations or becomes a tradition or part of a culture. Do not believe in something because a scripture says it is so. Do not believe in something believing a god has inspired it. Do not believe in something a teacher tells you to. Do not believe in something because the authorities say it is so. Do not believe in hearsay, rumour, speculative opinion, public opinion, or mere acceptance to logic and inference alone. Help yourself, accept as completely true only that which is praised by the wise and which you test for yourself and know to be good for yourself and others.” – The Buddha, The Kalama Sutta, Anguttara Nikaya 3.65, Sutta Pitaka, Pali Canon

“Believe nothing, no matter where you read it, or who said it, no matter if I have said it, unless it agrees with your own reason and your own common sense.”

The Buddha was originally called Siddhārtha Gautama and lived 2,500 years ago in Northern India. The term ‘Buddha’ means one who is ‘awake’, fully awake to his potential and to the world around him. The word ‘Buddhism’ is not how the teachings of the Buddha were originally known.

During our time at the centre we were fortunate to be introduced to the following concepts by Arthabandhu (“brother of the good”) our ordained teacher. He was pleasant and witty, calling the Buddha “metaphysically reticent” which is a phrase that has stayed with me.

The link here takes you to one of Arthabandhu’s speeches on Free Buddhist Audio – a site filled with talks, interviews, seminars, and question-and-answer sessions relating to Buddhism, from the early 1960s to the present day.

The Buddha taught his ‘Dharma’ or the truth as he saw it, and what he taught became known as the ‘Buddha-dharma’, the teachings of the Buddha. This body of teachings is what we in the West have come to call Buddhism. Buddhism is, essentially, all the teachings and practices developed by the Buddha and subsequent Enlightened disciples, that help the individual to become increasingly spiritually free, wise and compassionate, culminating ultimately in a profound state of knowledge known as Enlightenment.

(Hinduism, Jainism, Buddhism, and Sikhism all have the idea of dharma at their core, where it points to the purification and moral transformation of human beings.)

Because Buddhism does not include the idea of worshipping a creator god, I do not see it as a religion in the normal, Western sense. Buddhism is a path of practice and spiritual development leading to Insight into the true nature of reality. Buddhist practices like meditation are means of changing yourself in order to develop the qualities of awareness, kindness, and wisdom.

During my time at the centre I learnt about the life of the Buddha, how he described our own lives, the practices of loving kindness and generosity, Karma and rebirth in Buddhism and the nature of Nirvana. We also experienced two forms of meditation – The ‘mindfulness of breathing’ (a meditation for developing clarity and awareness) and the ‘Mettā bhāvanā’ (a practice for transforming our emotions, and for cultivating positivity and openness towards ourselves and others). I found the second particularly challenging after a bad day at work for example, but this just made it even more rewarding as it has helped me to have a more positive regard for others and has helped develop my intrapersonal skills.

This is similar to the idea of “unconditional positive regard”, a psychotherapy term which originates from the work of Carl Rogers. Rogers believed that for a person to “grow”, they need an environment that provides them with genuineness (openness and self-disclosure), acceptance (being seen with unconditional positive regard), and empathy (being listened to and understood). A simple introduction to Carl Rogers can be found here.

A few notes from my time at the centre:

The Centre is part of the Tiratana Buddhist Movement. (Tiratana meaning “Three Jewels”) These ‘jewels’ of Buddhism are where practitioners of Buddhism seek refuge, or that upon which one relies for his or her lasting happiness. The Three Jewels of Buddhism are the Buddha, meaning the mind’s perfection of enlightenment, the Dharma, meaning the teachings and the methods of the Buddha, and the Sangha, meaning those awakened beings who provide guidance and support to followers of the Buddha.

Mettā — loving kindness — is one of the “Four Immeasurables” or “Four Divine States” of Buddhism. These are mental states or qualities cultivated by Buddhist practice. The other three are compassion, sympathetic joy, and equanimity.

Mettā is sometimes translated as “compassion” but the Pali language makes a distinction between Mettā and Karuṇā, which also means “compassion”:

• Karuṇā connotes active sympathy and gentle affection, a willingness to bear the pain of others, and possibly pity.

• Mettā is a benevolence toward all beings that is free of selfish attachment. By practicing Mettā, a Buddhist overcomes anger, ill will, hatred and aversion.

One of the Buddha’s teachings I enjoyed learning about is the Mettā Sutta, which is sometimes called the Karaṇīyamettā Sutta after the opening word, Karaṇīyam, “(This is what) should be done”. The Chenrezig Project has a poster (.pdf file) of the Mettā Sutta to print out and display if you wish, I have a copy in my bedroom which inspired me to write this post when I looked at it this morning. The Theravada website ‘Access to Insight’ also provides a number of translations, including this one by noted scholar Thanissaro Bhikkhu. This is just a small part:

As a mother would risk her life

to protect her child, her only child,

even so should one cultivate a limitless heart

with regard to all beings.

Kukai’s Letter to a Nobleman in Kyoto

Kukai’s Letter to a Nobleman in Kyoto.

Related articles

- The Buddha’s Words on Kindness (Part 2) (inf0junkie.wordpress.com)

- The Karaṇīyamettā Sutta: The Buddha’s Words on Kindness (Part One) (inf0junkie.wordpress.com)